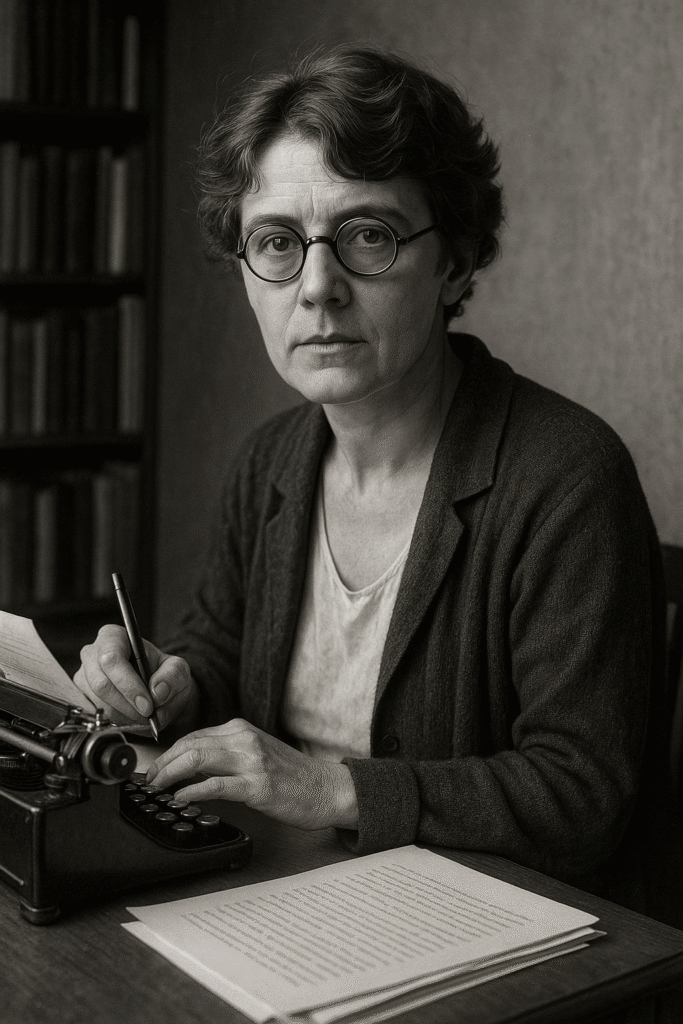

Hilda Doolittle as a Modernist Poet: A Revolutionary Feminine Voice

Hilda Doolittle, known by her pen name H.D., holds a powerful place in the story of American literature. Her contribution to modernist poetry remains undeniable. Although often overshadowed by male counterparts, Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet brought clarity, myth, and psychological depth into poetry. She reshaped the modernist movement through her unique blend of precision, symbolism, and feminism.

Early Life and Formation of a Poet

Born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in 1886, Hilda Doolittle grew up in a family steeped in science and art. Her father was a professor of astronomy, while her mother encouraged literary expression. This environment cultivated her early love for poetry. She attended Bryn Mawr College but left before finishing her degree.

During her time at Bryn Mawr, she met Ezra Pound, who later became a major influence. Their friendship helped launch her literary career. With his encouragement, she moved to London in 1911. There, her path as a poet took a groundbreaking turn.

The Birth of Imagism and Hilda Doolittle’s Role

Ezra Pound played a key role in introducing her work to the public. Specifically, he submitted her poems to Poetry magazine and coined the label “H.D. Imagiste.” As a result, this pivotal moment helped establish Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet. In contrast to earlier poetic styles, Imagism rejected vague emotionalism. Instead, it promoted clarity, sharp imagery, and economy of language.

Consequently, her first published poems stood out for their vivid, almost sculptural imagery. Notably, the 1916 collection Sea Garden remains a hallmark of early Imagist poetry. Through each poem, she carved emotion from precise language. Moreover, she avoided traditional rhyme and meter in favor of rhythm and free verse.

Let me know if you’d like me to revise other parts of the article similarly for smoother transitions.

Her short poem “Oread,” for example, uses nature-based commands to describe waves. Each word strikes with force. This stylistic clarity became her hallmark. Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet advanced Imagism not just by following its rules, but by redefining them through a female lens.

Psychological and Spiritual Evolution

World War I left a deep imprint on her worldview. She remained in Europe during the war, and the trauma around her changed her poetry. Her later work turned more inward. She moved beyond the strict Imagist framework, exploring myth, identity, and transformation.

She began psychoanalysis with Sigmund Freud in the 1930s. These sessions allowed her to confront personal fears, gender conflicts, and creative blocks. This inner journey marked a shift. Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet began addressing emotional complexity with greater confidence.

Her poems evolved from minimalist forms into expansive, layered narratives. She retained Imagism’s sharp edges but now combined them with deeper psychological and symbolic exploration.

Trilogy: The Modern Epic Reborn

Her wartime masterpiece Trilogy—written during World War II—includes The Walls Do Not Fall, Tribute to the Angels, and The Flowering of the Rod. This work blends modern war realities with ancient symbols. It portrays poetry as a form of spiritual resistance.

These poems do not only grieve loss. They explore survival. The speaker becomes both witness and healer. She invokes ancient gods, spiritual forces, and inner strength. In doing so, Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet presents a unique form of resilience: poetic faith amid destruction.

The Trilogy shows her mastery of rhythm, image, and myth. More importantly, it reveals how modern poetry could engage with history, politics, and spirit—all through a feminine voice.

Reimagining Myth through a Feminist Lens

Throughout her career, she used myth not as background but as a living force. Unlike her male peers, she reshaped classical stories to empower female characters. In Helen in Egypt (1961), she reclaims Helen of Troy. Rather than a passive beauty, Helen becomes a thinker, a mystic, and a symbol of inner conflict.

By rewriting myths, Hilda Doolittle gave agency to women erased by tradition. Her work challenges the masculine hero model so dominant in literature. She offers alternative visions—ones rooted in emotion, intuition, and symbolic rebirth.

Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet placed women at the center of stories they were once excluded from. Her voice redefined the role of myth in poetry. It became not just history retold, but a framework for modern identity and self-discovery.

Language and Form: Precision with Emotion

Her early poems carry the Imagist signature—short lines, few adjectives, and clean images. But even in these tight forms, emotion pulses. As her voice matured, her lines grew longer and her rhythms more meditative. Still, she never lost the sense of restraint.

She mastered the power of silence between words. She trusted her reader to feel what she hinted at. This gave her work a spiritual quality. Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet built tension through what she left unsaid.

Her control over language allowed her to tackle vast themes—love, war, gender, trauma—without losing balance. The result is poetry that feels both immediate and eternal.

Identity, Sexuality, and Creative Freedom

H.D. lived at a time when women’s voices were rarely centered in literature. Yet she remained true to herself. She had relationships with both men and women, including a lifelong partnership with the novelist Bryher. Their bond, creative and romantic, fueled much of her later work.

She never labeled her sexuality. However, her poems speak openly about desire, longing, and fluid identity. In this way, Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet became a quiet revolutionary. She broke taboos without slogans. She wrote about love, not politics—but her honesty had a radical impact.

Today, readers see her work as an early exploration of queer identity in American poetry. She opened doors simply by refusing to shut her own.

Reception and Legacy

During her lifetime, she was often grouped under Imagism and seen as a minor figure. However, feminist scholars in the 1970s rediscovered her work. They recognized its depth, complexity, and enduring relevance.

Today, Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet is studied alongside Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. Critics now see her not as a follower but as a leader in poetic innovation. Her work continues to inspire poets who explore identity, form, and myth.

Her influence can be seen in poets like Adrienne Rich, Judy Grahn, Susan Howe, and Anne Carson. Each found in H.D. a model of courage, control, and creativity.

Notable Works by Hilda Doolittle

Some of her most significant works include:

- Sea Garden (1916): A foundational Imagist collection

- Hymen (1921): Continued exploration of myth and gender

- Trilogy (1944–46): Epic reflection on war, spirituality, and survival

- Helen in Egypt (1961): A feminist reworking of classical mythology

- Hermetic Definition (1972): Deeply symbolic and personal exploration of identity

Each book offers a new layer of her voice. Together, they form one of the richest poetic legacies of the 20th century.

Why Hilda Doolittle Still Matters

Hilda Doolittle’s poetry offers something rare. It is both deeply personal and profoundly universal. She captures quiet moments with precision. She confronts massive forces—war, love, myth—with courage and control.

As a modernist, she broke new ground and reshaped the poetic landscape. As a seeker, she offered spiritual paths through words.

Hilda Doolittle as a modernist poet shows us how poetry can heal, question, and rebuild. Her work remains essential—not only for what it says, but for what it dares to become.

Quiz-Anglo-Saxon Period: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/06/22/anglo-saxon-period-literature-quiz/

Inferred Meanings and Examples with Kinds Explained:

https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/inferred-meaning-and-examples/

If by Rudyard Kipling: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/06/13/if-by-rudyard-kipling-questions-answers/

Mark Twain: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/mark-twain/

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.