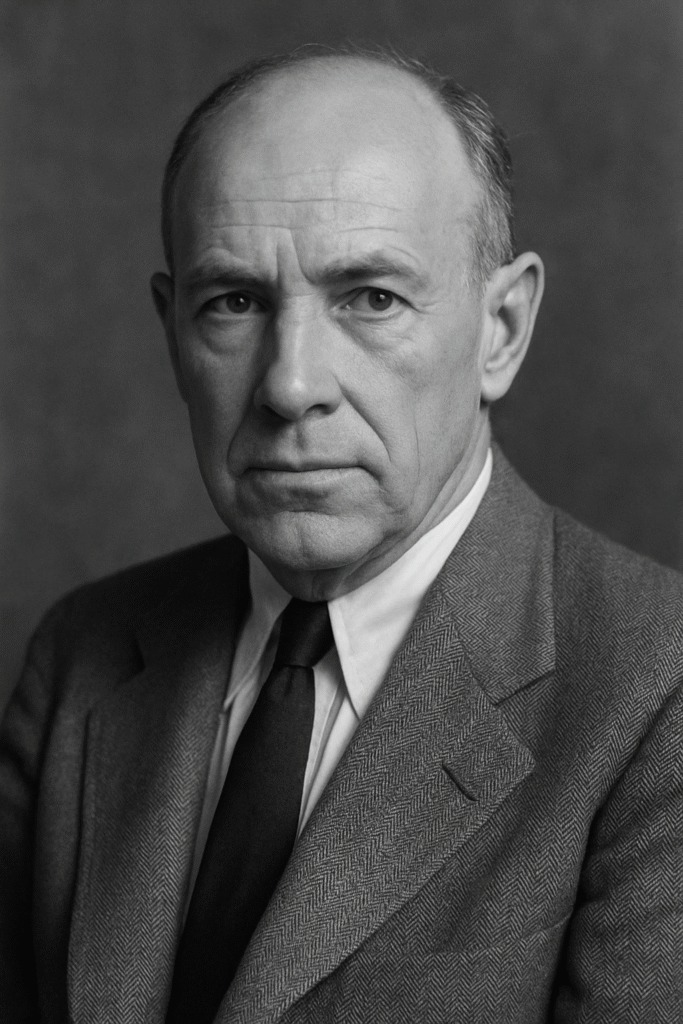

Archibald MacLeish as a Modernist Writer

Archibald MacLeish stands as a compelling figure in the canon of American modernist literature. As a poet, essayist, and public intellectual, he uniquely bridged the gap between high art and civic responsibility. His poetry is known for its formal experimentation, philosophical depth, and engagement with the pressing concerns of the 20th century. Although his name may not be as frequently invoked as T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound, MacLeish played a vital role in shaping American literary modernism. His work reflects the core concerns of the modernist movement—fragmentation, disillusionment, and the search for meaning in a rapidly changing world.

Early Influences and the Modernist Impulse

Archibald MacLeish was born in 1892 and educated at Yale and Harvard. Initially trained in law, he abandoned a promising legal career to pursue poetry. His decision to become a poet during a time of global upheaval reveals his deep commitment to art as a means of understanding and addressing the human condition. Influenced by classical literature, contemporary European poets, and fellow modernist Americans, MacLeish developed a style that fused tradition with innovation.

Living in Paris during the 1920s, MacLeish encountered the vibrant community of expatriate artists and writers. This experience was transformative. He absorbed the techniques of modernist experimentation, especially the use of fragmented narrative, symbol, and myth. Like many of his peers, he sought new forms of expression that could capture the complexity and uncertainty of modern life.

Experimentation with Form and Style

A hallmark of modernism is the rejection of conventional poetic forms in favor of experimentation. Archibald MacLeish embraced this principle. His poetry often defies traditional meter and rhyme, instead employing free verse, juxtaposition, and unexpected imagery. These elements are particularly evident in The Hamlet of A. MacLeish and New Found Land, where he plays with structure and syntax to convey modern anxieties and philosophical dilemmas.

MacLeish’s experiments were not mere stylistic flourishes. Rather, they reflected his belief that form should serve meaning. He argued that poetry must respond to the reality of its time, and if the world is fractured, then poetry must mirror that fragmentation. This idea is thoroughly modernist and aligns him with contemporaries like Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams.

“Ars Poetica” and the Modernist Philosophy of Art

Perhaps MacLeish’s most famous poem, Ars Poetica, is a compact expression of modernist poetics. The poem challenges traditional notions of meaning and argues for the autonomy of the poem itself. It opens with the memorable line: “A poem should be palpable and mute / As a globed fruit.” Each couplet that follows insists that poetry should not explain or teach, but rather be. This insistence on aesthetic autonomy is a core principle of modernism.

Ars Poetica also reflects the modernist distrust of didacticism and explicit moralizing. MacLeish suggests that true art transcends explanation; it evokes, suggests, and resonates without overtly instructing. His concluding line—“A poem should not mean / But be”—captures the spirit of a movement that valued ambiguity, depth, and multiplicity over clarity and certainty.

Engaging with Modern History and Politics

While many modernists turned inward or focused on the alienation of the individual, Archibald MacLeish maintained a strong sense of civic engagement. His poetry often responds to historical events, social issues, and the role of the artist in society. This tension between aesthetic purity and public responsibility adds a unique layer to his modernism.

During the Great Depression and World War II, MacLeish became increasingly involved in public service. He worked as Librarian of Congress, Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs, and as a speechwriter for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This blending of art and politics distinguishes him from some of his modernist contemporaries, who often avoided direct political engagement.

Still, even in his most public-facing roles, MacLeish remained committed to poetic integrity. His work did not become propaganda but rather used poetic form to explore civic and moral questions. In this way, he redefined modernist engagement—not as isolation from society, but as a deep and thoughtful interaction with it.

Myth and the Search for Meaning

Like many modernist writers, MacLeish turned to myth as a way to grapple with the spiritual crises of modernity. Myths, he believed, offered symbolic structures through which poets could make sense of chaos. In poems like Einstein, The Pot of Earth, and The Irresponsibles, he invokes ancient myths to illuminate contemporary struggles.

For example, The Pot of Earth uses the myth of Persephone to examine the cyclical nature of death and rebirth. In doing so, MacLeish connects timeless themes to modern despair, offering a form of existential reflection that is both personal and universal. This fusion of classical allusion with modern consciousness is deeply modernist in nature.

The Poetic Voice of a Nation

Another modernist trait in MacLeish’s work is his evolving poetic voice. His early poetry, heavily influenced by European symbolism and imagism, gradually gave way to a more direct, American idiom. In this shift, he mirrored the broader development of American modernism, which sought to establish a distinct literary identity separate from European traditions.

MacLeish’s later poems, such as those in Actfive and Other Poems, are marked by plain speech and philosophical reflection. They address the fragility of human knowledge, the uncertainty of truth, and the tension between freedom and order. These themes resonate with the concerns of other modernists, particularly those grappling with the aftermath of two world wars and the rise of totalitarian regimes.

A Poet of Contradictions

Archibald MacLeish’s modernism is defined by its contradictions. He was both a formal innovator and a defender of tradition. He wrote introspective verse yet served in public office. He embraced ambiguity but sought clarity in public discourse. These contradictions do not weaken his modernist identity; rather, they underscore the complexity and richness of his work.

Modernism itself is a movement of tensions—between past and present, form and chaos, alienation and engagement. MacLeish embodies these tensions in his life and writing. His poetry asks hard questions without offering easy answers, reflecting the disillusionment and intellectual rigor of his time.

Language as Symbol and Mystery

Language in MacLeish’s poetry is more than communication—it is mystery, symbol, and revelation. He often uses language not to define, but to suggest. This approach mirrors the modernist tendency to explore the limits of expression and the ambiguities of meaning. His choice of metaphor, syntax, and enjambment challenges readers to interpret and reflect.

For instance, in The End of the World, MacLeish presents a surreal circus scene as a metaphor for civilizational collapse. The poem’s dreamlike imagery and unexpected turn at the end convey a deep sense of instability and wonder. Such poems show his alignment with the modernist ethos: the world is no longer rationally ordered, and poetry must find new ways to reflect that reality.

Impact on American Literature

Although Archibald MacLeish’s work is less frequently anthologized today, his impact on American modernism remains significant. As a poet, editor, and policymaker, he influenced literary culture both through his art and his leadership. His tenure as Librarian of Congress brought serious attention to the importance of poetry and the humanities in national life.

MacLeish also mentored younger poets and defended the value of literature during times of war and crisis. He was a crucial figure in establishing poetry as a vital voice in American public discourse. His essays and speeches consistently argued that poets must speak truth, however complex or uncomfortable.

Conclusion: A Distinctive Modernist Voice

Archibald MacLeish’s contribution to modernist literature is both intellectual and emotional, civic and aesthetic. His poetry wrestles with the deepest issues of his time: the loss of faith, the rise of totalitarianism, the responsibilities of the artist, and the mystery of existence. Through formal innovation and thematic depth, he earned his place among the great modernist poets of the 20th century.

His ability to merge public service with poetic excellence is rare and admirable. While his modernism may not be as radical as that of Pound or as metaphysical as that of Eliot, it is no less profound. It is modernism grounded in humanity, ethics, and the enduring power of language. Archibald MacLeish remains a vital figure for anyone seeking to understand the full spectrum of American literary modernism.

Willa Cather as a Modernist Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/willa-cather-modernist-writer/

Application for Character Certificate: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/19/application-for-character-certificate/

Grammar Puzzle Solved: https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/connotative-and-denotative-meanings/

English Literature: http://englishlitnotes.com

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.