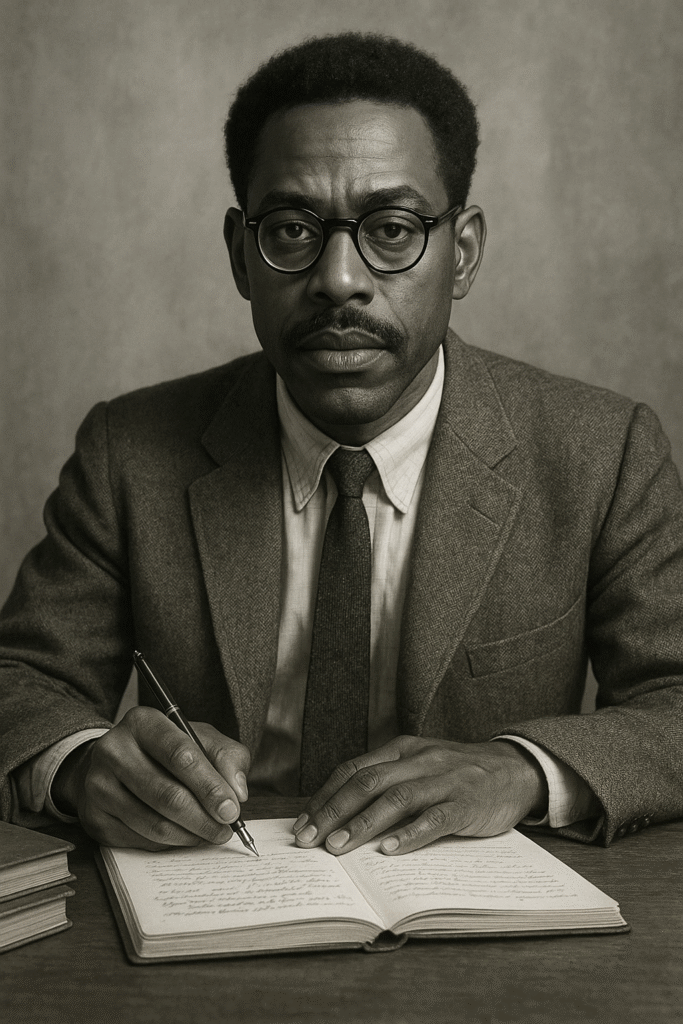

Sterling Allen Brown as a Modernist Writer

Sterling Allen Brown, a crucial figure in American literature, emerged during the Modernist period as a poet, critic, folklorist, and professor. While often associated with the Harlem Renaissance, Brown’s contribution to literary modernism is both significant and unique. He reshaped American poetry by introducing authentic Black vernacular, folk traditions, and Southern Black experience into modernist form and style. His commitment to capturing the lives of working-class African Americans, combined with his lyrical innovation and cultural awareness, places him firmly within the Modernist tradition.

Blending Tradition with Innovation

One of the defining features of literary modernism is the departure from conventional poetic forms and the embrace of experimentation. Sterling Brown adopted this approach by mixing traditional ballads, blues rhythms, spirituals, and jazz cadences with sharp social commentary. His poetry does not imitate white modernists like T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound; instead, it modernizes African American oral traditions, converting them into sophisticated poetic forms that challenge mainstream literary norms.

Brown’s work demonstrates that modernism does not need to be abstract or alienated from culture. Rather, it can be grounded in community, history, and identity. His 1932 collection, Southern Road, stands as a monumental achievement in this regard. Through it, Brown made a modernist statement rooted in realism, rhythm, and racial consciousness.

Southern Road: A Modernist Milestone

In Southern Road, Brown utilized free verse and flexible rhyme to recreate the musicality of blues and jazz. The collection is filled with portraits of everyday African Americans—sharecroppers, railroad workers, gamblers, mothers, and soldiers. Brown used dialect not as caricature but as a legitimate linguistic form that carried dignity, resilience, and power. This move was revolutionary for American modernist poetry.

The poem “Slim in Atlanta” illustrates how Brown employs repetition, blues structure, and narrative fragmentation to express systemic injustice:

They say it’s lack of wisdom

When you let the white man

Use you like a tool…

Here, Brown’s diction is straightforward, but the layering of irony and emotional complexity mirrors the modernist method of encoding critique within minimalist structure. Through his emphasis on voice, character, and mood, Brown expanded the limits of what modernist poetry could look and sound like.

Modernist Themes: Dislocation, Oppression, and Identity

Modernism often explores themes of alienation, fragmentation, and disillusionment. Sterling Brown tackled these themes through the lens of African American life in the Jim Crow South. His characters experience dislocation—not just physical but cultural and psychological. They exist in a fractured society that denies them full citizenship, dignity, and humanity.

However, Brown doesn’t simply dwell in despair. His poems reveal a quiet resistance, a survival of spirit, and an assertion of identity. This tension between suffering and resilience aligns him with other modernists who questioned established narratives, institutions, and ideals. His use of folk wisdom, communal memory, and oral storytelling allows him to modernize traditional themes without abandoning cultural specificity.

Folklore as a Modernist Tool

Sterling Brown’s deep appreciation for African American folklore allowed him to reshape modernist technique. Rather than adopt European myths or classical allusions, Brown used African American legends, idioms, and proverbs as narrative anchors. This gave his work a distinctive voice that modernized rural Black traditions in a literary context.

For example, the character John Henry—iconic in African American folklore—appears in Brown’s poetry as a symbol of strength and tragedy. His death in competition with a steam drill encapsulates the modernist anxiety about industrialization and human obsolescence. By repurposing folk tales through modernist framing, Brown reaffirmed the cultural worth of Black experiences while contributing to the broader literary movement.

Language and Rhythm as Modernist Innovation

Modernism in poetry is deeply concerned with language—its sound, structure, and limitations. Sterling Brown’s mastery of rhythm, especially blues and jazz cadences, helped him push these boundaries. His poetic lines often mimic spoken speech, but with calculated pauses, repetition, and variation that create a dynamic, musical quality.

In “Ma Rainey,” Brown reflects on how music touches the soul of its listeners:

When Ma Rainey

Comes to town

Folks from anyplace

Miles aroun’

From Cape Girardeau

Poplar Bluff

Flocks in to hear

Ma do her stuff…

This poem celebrates not just a legendary blues singer, but also the power of music to create community, relieve pain, and express shared experience. The line breaks, internal rhymes, and colloquial language show how Brown turned modernist concerns—identity, alienation, social fragmentation—into a communal and rhythmic art form.

Political Consciousness and Literary Activism

Another modernist quality in Brown’s work is his political awareness. While modernism often critiques the modern world, Brown’s critique is grounded in systemic racism and economic oppression. His poetry refuses to romanticize Black suffering or present simplistic solutions. Instead, it demands recognition of structural inequalities while maintaining faith in cultural strength.

Unlike many of his modernist contemporaries, Brown remained deeply connected to education and activism. He taught at Howard University for over 40 years and helped shape generations of Black writers and thinkers. His influence extended into public policy and civil rights, reflecting a socially grounded version of literary modernism.

Oral Tradition and Modernist Voice

Brown’s poetry is deeply rooted in the African American oral tradition, a feature that aligns with modernist experimentation in voice and perspective. His speakers range from the grieving mother to the defiant worker, from the weary preacher to the hopeful lover. These voices are distinct, authentic, and emotionally rich.

By using persona and monologue, Brown echoes modernist interest in subjectivity and fractured identity. Yet his poems never lose clarity. They remain accessible even as they grapple with profound questions of injustice, survival, and cultural pride. This dual clarity and complexity exemplify the best of modernist technique.

Sterling Brown and the Harlem Renaissance

Although he is often placed within the Harlem Renaissance, Sterling Brown’s contribution to literary modernism should not be overlooked. The Harlem Renaissance was itself a modernist movement—a cultural revolution that redefined Black identity through innovation in art, literature, and music. Brown, with his commitment to form, voice, and folk tradition, was central to this redefinition.

He differed from some Harlem Renaissance writers by focusing on the rural South rather than the urban North. This focus broadened the scope of modernist literature by including voices and experiences often marginalized in both white and Black literary circles. Brown modernized Southern Black narratives, integrating them into the evolving American literary identity.

Lasting Influence and Legacy

Sterling Brown’s influence can be seen in later generations of poets, particularly the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and contemporary spoken word artists. His commitment to truth-telling, rhythmic language, and community storytelling has inspired writers like Amiri Baraka, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Natasha Trethewey.

He showed that modernist poetry need not be obscure or disconnected from social reality. Instead, it could speak in the language of the people, reflecting their joys, sorrows, and struggles with nuance and integrity. In doing so, Brown reshaped the possibilities of American poetry.

Modernism Reimagined Through Cultural Specificity

Sterling Brown’s approach to modernism was distinct because it was rooted in Black cultural traditions. He demonstrated that modernism was not a single, monolithic movement, but a flexible framework that could accommodate diverse experiences and styles. By reimagining modernist concerns through African American lenses, Brown enriched the entire movement.

He challenged the Eurocentric norms of literary modernism, proving that the modern world could be interrogated just as powerfully from a Southern porch as from a Parisian café. His authenticity, resistance to stereotype, and elevation of marginalized voices were both acts of literary innovation and cultural reclamation.

Conclusion: Sterling Brown’s Place in Modernism

Sterling Allen Brown deserves recognition not just as a key figure in African American literature but as a central contributor to American literary modernism. His poetic innovations in form, language, and rhythm, along with his unflinching exploration of race, history, and identity, align him with the core principles of the modernist movement.

What sets Sterling Allen Brown apart is his ability to merge the local with the universal, the folk with the intellectual, and the poetic with the political. He showed that modernist poetry could be grounded in everyday language and experience while still grappling with profound existential and cultural questions. Through his work, Sterling Allen Brown redefined what it meant to be a modernist writer in America.

Archibald Macleish as a Modernist Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/archibald-macleish-modernist-writer/

Application for Change of Subjects: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/19/change-of-subjects/

Grammar Puzzle Solved: https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/connotative-and-denotative-meanings/

English Literature: http://englishlitnotes.com

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.