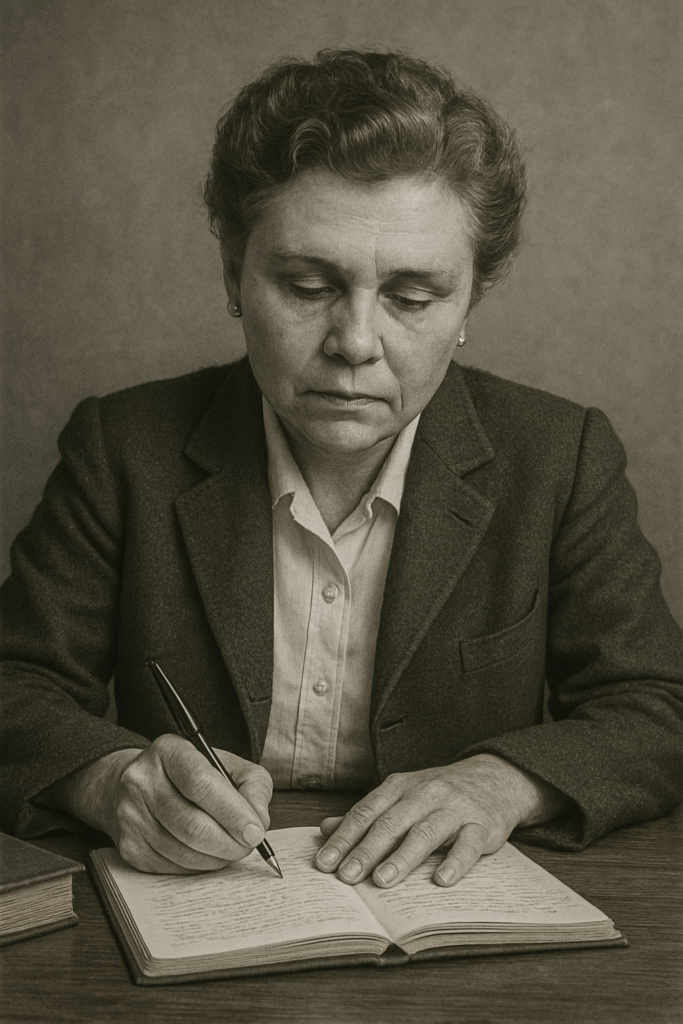

Elizabeth Bishop as a Modernist Writer (1911–1979)

Elizabeth Bishop as a modernist writer is one of the most distinctive and compelling voices in 20th-century American poetry. Though sometimes classified as a transitional figure between modernism and postmodernism, Bishop is widely regarded as a modernist poet due to her precision, formal restraint, and philosophical depth. Her work is marked by a keen observational eye, a profound sense of geography and displacement, and a subtle emotional resonance. In a literary landscape dominated by the radical innovations of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Wallace Stevens, Bishop carved out her own unique space, one that balanced clarity with complexity and objectivity with emotional undercurrents.

The Modernist Context and Bishop’s Emergence

Elizabeth Bishop came of age during the later years of literary modernism. By the time her first collection, North & South (1946), appeared, many of modernism’s foundational texts had already been published. The innovations of Eliot, Pound, and others had set new standards for poetic form, fragmentation, and allusion. However, Bishop did not mimic these methods wholesale. Instead, she absorbed modernist sensibilities—especially the emphasis on observation, impersonality, and formal discipline—while rejecting the opacity and grandiosity that marked some of her contemporaries’ work.

Bishop’s mentor, Marianne Moore, herself a modernist, greatly influenced her in the use of precise imagery and attention to natural detail. Both poets emphasized the importance of description as a means of moral and philosophical inquiry. For Bishop, modernism was not about radical disjunction or mythic allusion but about attending carefully to the world, especially its overlooked or mundane aspects.

The Precision of Language and Detail

One of the hallmarks of Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry is her meticulous attention to detail. Her descriptive powers are unrivaled, and her ability to render scenes, objects, and emotions with almost scientific precision places her firmly within the modernist tradition. In poems like “The Fish,” Bishop examines a simple act—catching and releasing a fish—with extraordinary observational focus:

He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely.

The poem goes on to catalog the fish’s physical attributes in almost forensic detail. This method echoes the modernist commitment to exactitude and depersonalization. Bishop avoids sentimentality; instead, she builds emotion through description. The reader is invited not into the poet’s psyche directly but into the external world that triggers introspection.

This focus on the external world is a defining modernist trait. Like Imagist poets before her, Bishop believed that the poem should offer a direct treatment of the thing. In her hands, this became a powerful tool for exploring psychological and existential themes. Her eye for detail is not merely aesthetic; it is epistemological. Through close observation, Bishop attempts to understand the world and her place in it.

Geography and Displacement

Another essential element of Bishop’s modernism is her engagement with geography and displacement. Throughout her life, Bishop traveled extensively—living in the United States, Brazil, and Canada, among other places. Her poetry often reflects this movement, both physically and emotionally. Poems like “Questions of Travel,” “Arrival at Santos,” and “The Map” explore themes of exile, belonging, and the instability of home.

Modernist literature frequently addresses the dislocation and fragmentation of modern life. Bishop’s treatment of place is deeply modernist in its complexity. She is interested not only in where things are but in how they are represented and perceived. In “The Map,” she writes:

Topography displays no favorites; North’s as near as West.

This dispassionate tone belies the poem’s emotional stakes. The map becomes a metaphor for perception, for how we understand and navigate the world. Bishop questions the reliability of both cartographic and poetic representation. This interrogation of perception aligns her with other modernists who challenged the notion of objective reality.

Impersonality and Emotional Control

T.S. Eliot, in his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” argued for the impersonality of the poet. Elizabeth Bishop as a modernist writer embodies this principle. Her poems are rarely confessional. While deeply emotional, they are often mediated through observation, allegory, or metaphor. She eschews overt expressions of feeling in favor of restraint and irony.

For instance, in her elegy for her friend Robert Lowell, “North Haven,” Bishop mourns with delicacy and distance. She writes:

The island is exactly what it was, it still is, only you have gone away.

There is sorrow here, but it is expressed through understatement and precise observation of the unchanged landscape. This technique is quintessentially modernist: the emotional weight is carried by implication rather than declaration. Bishop’s control over tone and voice allows her to explore complex emotional terrain without descending into sentimentality.

The Role of Form and Structure

Though Bishop often wrote in free verse, many of her poems exhibit formal constraints and traditional structures. She frequently used rhyme, meter, and fixed forms like the villanelle and sestina. This formal discipline reflects her modernist belief in the importance of structure and technique.

One of her most famous poems, “One Art,” is a villanelle—a challenging form that requires repeated lines and a strict rhyme scheme. The poem explores the theme of loss with increasing intensity:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master; so many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

As the poem progresses, the losses become more personal, culminating in the loss of a beloved. Yet the form holds, even as the speaker’s composure wavers. The tension between the rigid structure and the raw emotion creates a powerful modernist effect—suggesting that order can barely contain chaos.

Bishop’s use of form is not nostalgic but functional. She uses traditional structures to explore modern themes—loss, identity, displacement, and perception. This synthesis of old and new is a modernist hallmark.

Visual Arts and Ekphrasis

Elizabeth Bishop as a modernist writer had a strong interest in visual art, and this interest deeply influenced her poetic technique. Her poems often function like paintings, focusing on composition, color, and detail. This painterly quality reflects the modernist interest in cross-disciplinary inspiration.

In “Poem,” she describes a small landscape painting in careful, loving detail. The poem becomes an act of looking, of appreciating the subtle beauty of the everyday. It is also a meditation on perception, memory, and the relationship between art and life—central concerns of modernism.

This ekphrastic impulse—the use of visual art as a subject for poetry—links Bishop to other modernists like William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore. But her approach is distinct in its intimacy and humility. She does not seek to explain or transcend the artwork; she dwells within it, allowing the object to speak.

Influence of Travel and Exile

Bishop’s time in Brazil had a profound impact on her work. Living outside the United States allowed her to view her homeland from a distance, a perspective shared by many modernist expatriates. However, unlike Pound or Eliot, Bishop did not adopt a mythic or universalizing tone. Instead, she remained focused on the particular, the local, and the personal.

Her Brazilian poems—such as “Brazil, January 1, 1502” and “Manuelzinho”—explore the complexities of colonialism, cultural exchange, and identity. These poems resist easy categorization; they are both admiring and critical, affectionate and ironic. This ambivalence is deeply modernist, reflecting a world in which binaries collapse and certainty is elusive.

The Ordinary as Extraordinary

Perhaps Bishop’s greatest modernist achievement is her ability to find the extraordinary in the ordinary. Her subjects are often humble—filling stations, fish, maps, sandpipers—but she imbues them with meaning through careful observation and linguistic precision. This transformation of the mundane into the profound is a central modernist project.

In “The Filling Station,” for example, Bishop describes a dirty, greasy gas station with an almost loving attention to detail. She concludes:

Somebody loves us all.

The final line is both startling and tender. It emerges not from abstract theology but from the careful depiction of a small, domestic touch—a doily in a grimy setting. The modernist tension between chaos and order, despair and hope, is resolved here not through ideology but through attention and care.

Conclusion: Bishop’s Lasting Modernist Legacy

Elizabeth Bishop’s contribution to literary modernism is both profound and distinct. She embraced many modernist ideals—formal discipline, impersonality, observational precision—while avoiding the obscurity and abstraction that characterized some of her peers. Her poetry is grounded in the real world but open to philosophical and emotional complexity. She found new ways to express timeless concerns—loss, love, displacement, identity—through the lens of the everyday.

Her restraint, humility, and attention to craft have influenced generations of poets. Writers like Seamus Heaney, James Merrill, and Louise Glück have cited her as a formative influence. Her legacy lies not only in her poems but in her approach: a modernist sensibility shaped by clarity, compassion, and a deep respect for the power of language.

In a century of noise and fragmentation, Bishop’s voice remains clear, steady, and vital. She reminds us that poetry can be both rigorous and humane, precise and profound. In this balance, Elizabeth Bishop as a modernist writer exemplifies the best of American modernism.

Carl Sandburg as a Modernist Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/carl-sandburg-modernist-writer/

Application for Fee Concession: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/20/application-fee-concession/

Grammar Puzzle Solved: https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/connotative-and-denotative-meanings/

English Literature: http://englishlitnotes.com

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.