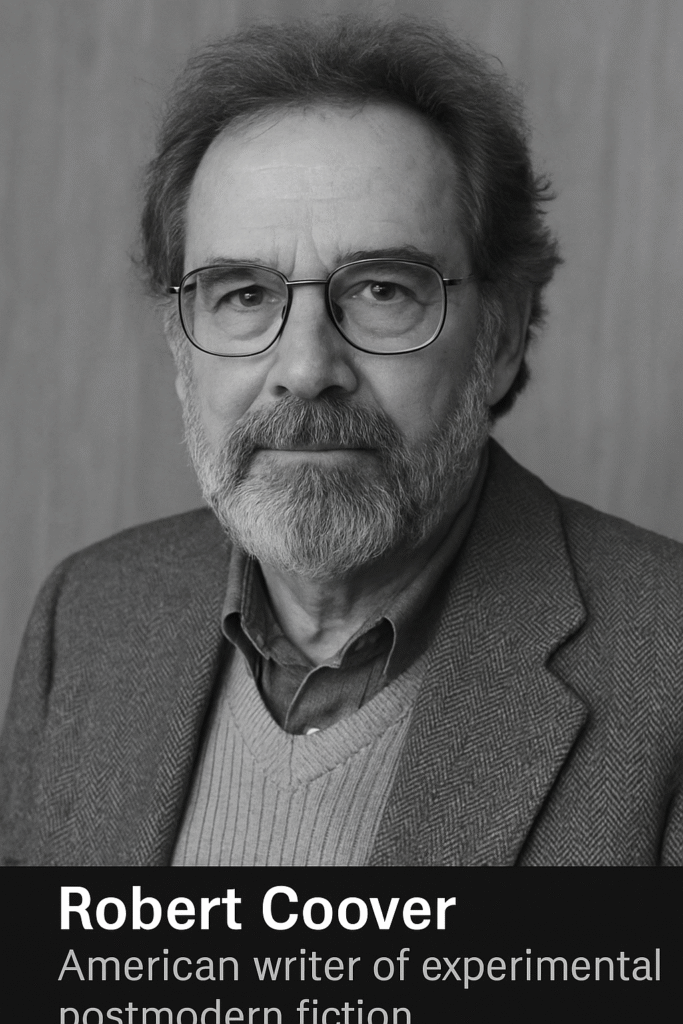

Early Life, Academic Roots, and Intellectual Curiosity

Robert Coover was born on February 4, 1932, in Charles City, Iowa. Raised in a middle-class family, he showed early interest in language, storytelling, and irony. His educational path shaped his future as a boundary-breaking novelist.

He attended Southern Illinois University and then went on to Indiana University. Later, he earned a master’s degree from the University of Chicago. During his studies, Coover explored classic literature, modernist fiction, and media theory. These interests shaped his experimental vision.

Coover didn’t pursue immediate fame. Instead, he studied deeply. He spent time teaching, researching, and writing quietly. His literary voice matured slowly. When he published, he broke every rule of conventional narrative.

Early Publications and Immediate Disruption

Robert Coover American writer didn’t debut with realism. He didn’t offer traditional plots or familiar characters. From his earliest works, he disrupted storytelling.

His first major publication, The Origin of the Brunists (1966), won the William Faulkner Foundation Award. The novel told the story of a mining disaster and a bizarre religious cult that rises afterward. While the premise seemed conventional, Coover’s approach was not.

He didn’t offer clear heroes. He didn’t provide moral conclusions. He blurred belief and delusion. He questioned the need for structure and order. He filled the book with contradictions.

This first novel hinted at the experimental methods he would later master. It showed early signs of his satire, irony, and refusal to moralize.

The Universal Baseball Association: Play, Power, and Metafiction

In 1968, Coover released The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop. This novel placed him among key postmodern authors. The story followed a lonely accountant who creates a fictional baseball league.

His imagination deepens. He names players, records scores, and writes histories. Soon, the game overtakes reality. The fictional events control his emotions, beliefs, and actions.

Through this story, Coover examined God, creation, storytelling, and madness. He questioned authorial power. He explored the limits of control. He asked what happens when fiction becomes more meaningful than life.

The novel blended metafiction, satire, and pathos. It showed Coover’s ability to use absurd premises for serious inquiry. It also marked his first major use of narrative games.

Breaking Myths in Pricksongs and Descants

Coover reached artistic maturity in 1969 with Pricksongs and Descants, a collection of experimental short stories. These stories tore apart myths, fairy tales, and narrative traditions.

He rewrote Little Red Riding Hood with sexual subtext. He fractured biblical episodes. He looped fairy tales endlessly. Each story questioned meaning. Each piece laughed at expectation.

Coover didn’t just parody myths. He deconstructed them. He revealed their hidden violence, absurdity, and cultural power. He exposed how narratives shape identity, morality, and memory.

This collection made clear: Robert Coover American writer rejected realism. He chose distortion. He embraced play. He saw fiction as a political and philosophical tool.

Satire and Structure in The Public Burning

In 1977, Coover released The Public Burning, arguably his most controversial work. The novel fictionalized the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, accused of spying for the Soviet Union.

Coover narrated the story through a fictionalized version of Vice President Richard Nixon. The novel included surreal figures like “Uncle Sam” as a demonic clown. It blended fact, fantasy, history, and myth.

It didn’t simply criticize American politics. It mocked national myths. It exposed media manipulation. It satirized paranoia and spectacle.

The novel’s most radical gesture was stylistic. Coover layered voices, shifted genres, and distorted timelines. He made the reader uncomfortable and aware.

The government wasn’t amused. Legal fears delayed the book’s publication. Yet critics hailed it as genius. It confirmed Coover’s place as a daring literary force.

Fiction as Game and Ritual

Robert Coover American writer viewed fiction as both play and ritual. His works didn’t aim for truth. They aimed for exposure. He used repetition, parody, fragmentation, and exaggeration.

Many of his stories repeat familiar tropes—hero, journey, seduction, judgment. But he twists them. He loops them. He empties them of moral certainty.

He often inserts the storyteller as a manipulator. He shows the seams of fiction. He forces readers to question every plot turn, every voice, every motive.

His stories often end in uncertainty. Or they never end at all. They loop. They mirror themselves. They reject closure.

Coover believed storytelling was an illusion. Yet he loved the illusion. He didn’t destroy narrative to mock it. He did so to free it.

Gerald’s Party: Satire, Sex, and Surveillance

In 1986, Coover released Gerald’s Party, a novel set during a chaotic house party. A woman is murdered, but the crime becomes background noise. Characters engage in sex, speech, spectacle, and surreal games.

The novel unfolds in real time. It shifts abruptly between events, voices, and memories. Coover uses confusion to reflect overstimulation. Everything becomes performance. Truth dissolves.

The novel explores voyeurism, desire, distraction, and chaos. Coover shows how society turns murder into entertainment. He critiques how media distorts reality.

The book feels like a parody of detective fiction. But it also attacks modern attention spans. Nothing holds still. Nothing matters for long.

Embracing Digital Literature and New Forms

Unlike many literary figures of his generation, Robert Coover embraced new media. He didn’t fear technology. He saw it as a chance to break even more rules.

In the 1990s, he began promoting hypertext fiction. These digital narratives allowed readers to choose paths, jump scenes, and shape stories. Coover championed writers like Michael Joyce, author of Afternoon, a story.

He called hypertext “literature’s liberation.” He believed it matched postmodern reality—fragmented, nonlinear, user-driven. Coover didn’t just theorize. He wrote his own digital experiments. He taught courses on electronic literature at Brown University.

He helped establish the Electronic Literature Organization. He mentored young writers exploring interactive fiction, digital poetry, and narrative AI. Coover kept pushing boundaries—now in pixels.

Later Works and Continuing Evolution

Coover’s later works never lost boldness. He continued rewriting myths, history, and genre fiction.

In The Adventures of Lucky Pierre (2002), he explored pornography and censorship. In The Brunist Day of Wrath (2014), he returned to characters from his debut, exploring cult violence and apocalyptic obsession.

His style stayed experimental. His themes stayed urgent. He wrote against power, myth, and ideological comfort. He never softened.

Even in his eighties, Coover remained innovative. He embraced interactive media, theater, and performance. He never retreated into nostalgia.

Themes: Myth, Media, Power, and Desire

Robert Coover American writer tackled timeless themes with unique technique. He questioned myth, exposed media, and dissected power.

He showed how stories shape ideology. He revealed how media turns horror into theater. He mocked moral certainty. He mocked the audience’s need for control.

Desire also haunted his work—desire for meaning, pleasure, stability. He showed how that desire created gods, wars, fairy tales, and history books.

But he never offered a replacement. He didn’t provide moral solutions. He left questions open. He left endings suspended.

Coover didn’t destroy meaning. He multiplied it. He let readers enter the chaos.

Voice, Language, and Form

Coover’s language crackles. It’s energetic, ironic, and playful. He bends syntax. He switches tones. He changes genre within pages.

His form reflects his themes. He breaks linear time. He removes narrators. He rewrites familiar texts. He uses unreliable voices.

His style isn’t about showing off. It’s about disruption. It forces attention. It reflects distortion. It becomes political.

His language is never static. It performs. It dances. It contradicts.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

Robert Coover American writer reshaped postmodern literature. He didn’t just innovate style. He redefined purpose.

He showed fiction doesn’t need plot. It doesn’t need moral. It needs imagination. He made story into experiment. He made reading into experience.

He mentored students. He built platforms for digital authors. He kept fiction alive, even as culture changed.

Writers like David Foster Wallace, Jennifer Egan, and Mark Danielewski drew from his methods. Critics placed him with Barth, Pynchon, and Gaddis. He belongs in every postmodern hall of fame.

Final Thoughts

Robert Coover American writer never settled. He broke myths, laughed at gods, and opened new paths. He taught readers not to trust stories—but also not to abandon them.

He showed fiction as art, as game, as mirror. His words still twist, reflect, question, and gleam.

He didn’t offer truth. He offered tools. He gave readers the freedom to see.

Samuel Butler, Restoration Period Writer: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/07/03/samuel-butler-restoration-period-writer/

Thomas Pynchon Postmodern Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/thomas-pynchon-postmodern-writer/

The Thirsty Crow: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/10/the-thirsty-crow/

Subject-verb Agreement-Grammar Puzzle Solved-45:

https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/subject-verb-agreement-complete-rule/

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.