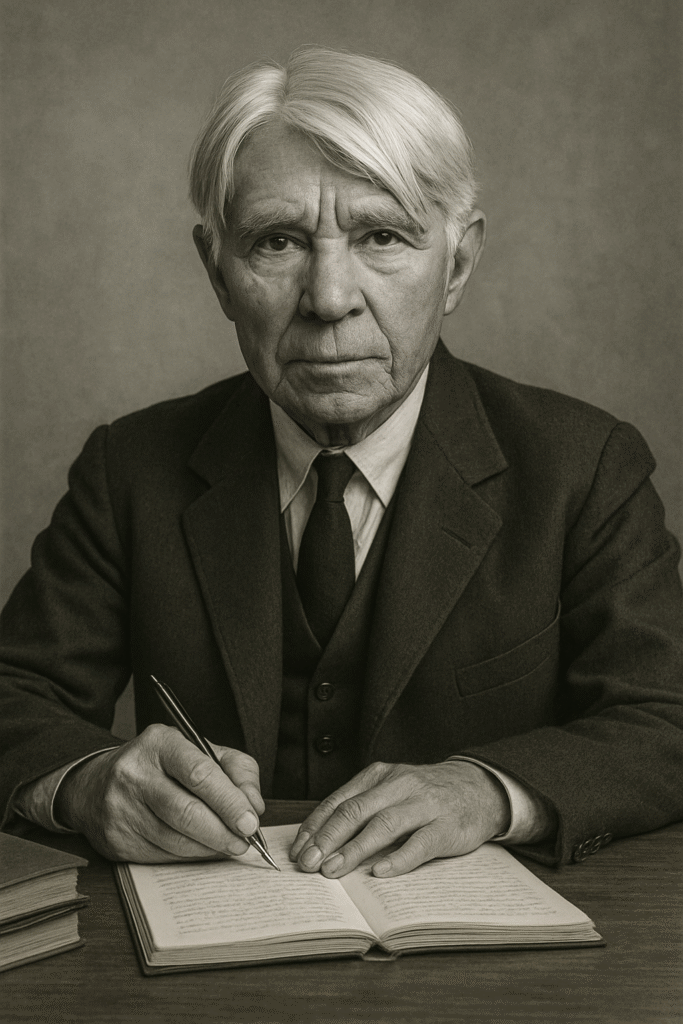

Carl Sandburg as a Modernist Writer

Carl Sandburg, a towering figure in early 20th-century American poetry, redefined the poetic landscape through his free verse, working-class themes, and distinctly American voice. Often linked with literary modernism, Sandburg stood apart from more esoteric contemporaries like T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound. Instead, he developed a grounded and accessible form of modernism, one that embraced democracy, urban experience, and the dignity of ordinary people. His deep empathy for American laborers and his experimentation with poetic form make him a significant contributor to American modernist literature.

Rooted in the American Experience

Sandburg’s poetry is inseparable from the American experience. Born in Galesburg, Illinois, to Swedish immigrant parents, Sandburg grew up in working-class surroundings. He held numerous blue-collar jobs—porter, house painter, milkman, and laborer—which provided firsthand insight into the struggles of everyday Americans. These experiences profoundly shaped his poetry, giving him an authentic voice that resonated with readers across class lines.

While modernism often leaned toward intellectual abstraction, Sandburg’s poetry emphasized the concrete and the communal. He saw beauty in factories, smoke, sweat, and steel. For Sandburg, the American city—especially Chicago—was not a symbol of moral decay but of energy, ambition, and complexity. In embracing this vision, he reimagined the modernist poetic subject.

“Chicago” and Urban Modernism

Carl Sandburg’s most iconic poem, “Chicago,” is a modernist landmark. Written in muscular, vibrant free verse, the poem addresses the city directly:

“Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler…”

Sandburg’s celebration of Chicago’s gritty vitality contrasts sharply with traditional poetic subjects like nature or nobility. Instead, he elevates labor, industry, and urban life, aligning himself with modernism’s rejection of Victorian sentimentality. His use of cataloging, repetition, and unorthodox rhythms exemplifies the modernist shift toward experimental form and subject matter.

“Chicago” reflects the fragmented, industrialized world that modernists sought to capture. Yet, Sandburg also injects pride and defiance into the portrait—he does not mourn the city’s flaws; he embraces them as part of its strength. This bold embrace of the working city stands as one of modernism’s most humanistic achievements.

Free Verse and Democratic Form

Sandburg’s commitment to free verse places him squarely within the modernist tradition. Like Walt Whitman, whom he deeply admired, Sandburg rejected rigid meter and rhyme schemes. He believed that poetry should reflect the rhythm of common speech and the variety of American experience.

This use of free verse was not only a stylistic choice but also a political one. Sandburg wanted to democratize poetry—make it available to all, not just the elite. In doing so, he modernized the poetic form by liberating it from strict formal constraints and rooting it in everyday language and imagery.

In his collection Cornhuskers (1918), Sandburg expands this technique to include meditations on war, nature, and the soul of the American Midwest. The unadorned, lyrical quality of his poetry makes it both modern and timeless, simple yet deeply evocative.

Poetry of the Common People

Modernism often addresses themes of alienation and existential uncertainty. Sandburg embraced these themes but reframed them through the lives of laborers, soldiers, farmers, and migrants. His poems reveal the dignity and despair of the working class, offering a collective voice rarely heard in traditional poetry.

For example, in “Masses,” Sandburg writes:

“Among the mountains I wandered and saw blue haze and red crag and was amazed;

On the beach where the long push under the endless tide manipulated sand

I saw the dust of all men…”

These lines reflect both the grand scope of human existence and its fleeting nature. Sandburg’s blending of humanist sentiment with modernist imagery connects the individual to larger social and cosmic patterns—an enduring trait of modernist inquiry.

War and Historical Reflection

Sandburg’s role as a journalist during World War I and his later writings on Abraham Lincoln reveal another modernist dimension: the use of history and reportage to understand the present. His Complete Poems and Rootabaga Stories (written for children but thematically layered) engage with the trauma of war, the disillusionment with politics, and the endurance of human spirit.

In “Grass,” one of his most haunting poems, Sandburg uses nature as a metaphor for historical erasure:

“Pile the bodies high at Austerlitz and Waterloo.

Shovel them under and let me work—

I am the grass; I cover all.”

The chilling minimalism of the poem, its anonymity, and its repetition reflect modernism’s focus on loss, memory, and the breakdown of historical continuity. The poem’s compact power illustrates how Sandburg merged poetic simplicity with philosophical depth—a quintessential modernist aim.

Champion of American Modernist Identity

Unlike expatriate modernists who sought inspiration in Europe, Sandburg remained rooted in American soil. He championed a distinctly American modernism—practical, hopeful, and muscular. His poetry resists the despair seen in some modernist works by offering an alternative: one that sees value in progress, in struggle, and in the collective will.

This outlook made Sandburg both accessible and influential. He spoke at labor rallies, gave public readings, and became a cultural icon. While critics sometimes dismissed him for being too populist or sentimental, his influence endured. He proved that modernism could speak to the masses without losing complexity or vision.

Music and Prose: Expanding the Modernist Mode

In addition to poetry, Sandburg experimented with prose and music. He was a folk music collector, performer, and guitarist. His American Songbag (1927) compiled traditional American songs from diverse ethnic and social backgrounds, reinforcing his belief in cultural inclusivity.

He also published biographies, including his Pulitzer Prize-winning Abraham Lincoln: The War Years. While this historical work may seem separate from modernist literature, it reflects his belief in the poet as chronicler and shaper of national identity—a belief shared by other modernists like Ezra Pound and Hart Crane.

Sandburg’s prose exhibits many modernist traits: fragmentation, juxtaposition, and polyphony. His work draws on multiple genres, blurring the lines between fact and myth, narrative and lyricism.

Modernist Vision Rooted in Democracy

Sandburg’s poetic vision was grounded in democracy and diversity. He saw America as an unfinished poem—open to revision, populated by varied voices, and moving toward justice. His optimism, while unusual for a modernist, did not blind him to suffering or inequality. Instead, it gave him the strength to confront those realities with honesty and hope.

He also understood the power of symbols. The American flag, railroads, skyscrapers, and steel mills become more than mere objects in his poetry—they are metaphors for aspiration, failure, and transformation. This symbolic layering connects him to the modernist fascination with myth and archetype.

Criticism and Reappraisal

During his lifetime, Sandburg was both celebrated and critiqued. Some literary modernists considered his work too plain, too journalistic. Yet, in retrospect, his style represents a vital strain of American modernism—one that balanced experimentation with accessibility, and individual insight with collective voice.

Later critics have praised his authenticity, musicality, and unwavering commitment to the American story. His poetry is studied not only for its literary merit but also for its contribution to national consciousness during times of upheaval and change.

Lasting Influence

Sandburg’s influence extends beyond literature. He helped shape the American understanding of labor, identity, and national purpose. His ability to capture the pulse of a nation—its rhythm, fears, and dreams—makes his work perpetually relevant. Poets such as Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Philip Levine have drawn inspiration from Sandburg’s focus on the working class and his fusion of poetic freedom with political conscience.

Moreover, Sandburg opened doors for poets who dared to write plainly and boldly, without sacrificing emotional or intellectual depth. His life and work remain testaments to the idea that poetry can be both art and action.

Conclusion: Carl Sandburg’s Place in Modernist Literature

Carl Sandburg stands as a foundational voice in American modernist poetry. While he may not fit the mold of the high modernists, his poetry embodies the core ideals of the movement: innovation, realism, and cultural engagement. His choice to foreground ordinary Americans, his adoption of free verse, and his embrace of democratic themes redefined what poetry could be.

His work does not reside in abstract theory or esoteric symbolism—it lives in factories, fields, train yards, and crowded cities. Yet, in these settings, he found lyrical beauty, moral complexity, and timeless truth. Carl Sandburg’s modernism is one of grounded vision, rooted in the soil of a restless, striving nation.

Sterling Allen Brown as a Modernist Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/sterling-allen-brown-modernist-writer/

Application for Remission of Fine: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/20/application-remission-of-fine/

Grammar Puzzle Solved: https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/connotative-and-denotative-meanings/

English Literature: http://englishlitnotes.com

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.