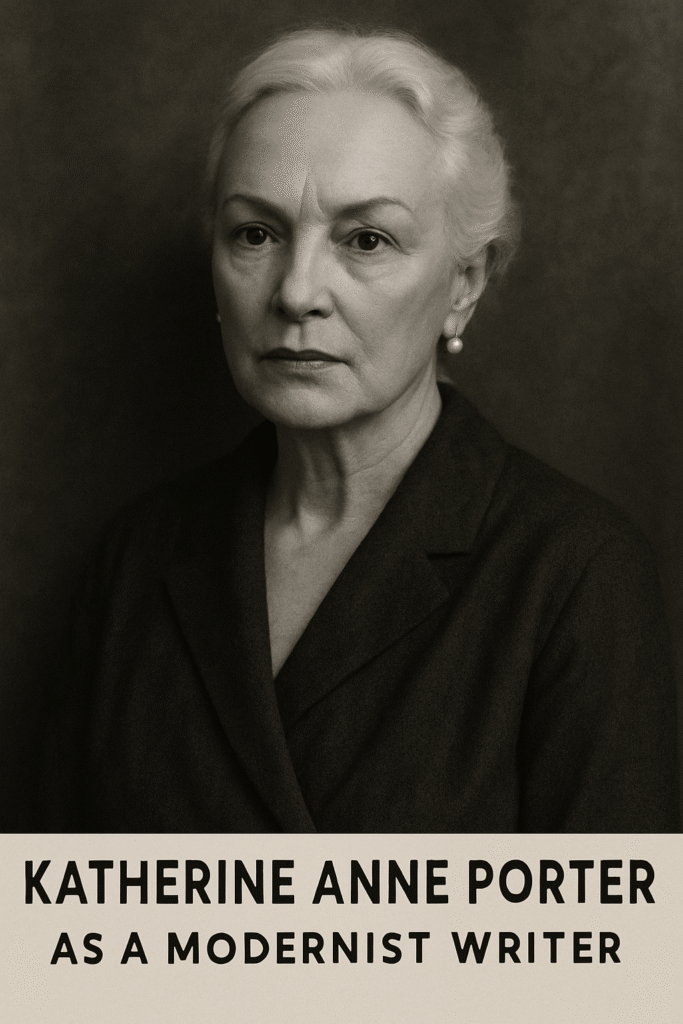

Katherine Anne Porter as a Modernist Writer

Katherine Anne Porter stands among the most brilliant and quietly influential figures of American modernist literature. Although she is best known for her short fiction rather than novels, her work embodies the defining characteristics of the modernist movement. Through her sparse but evocative prose, psychological insight, and structural innovation, Porter captured the spiritual uncertainties and fractured realities of the early 20th century. Her stories are intense, symbolic, and layered with meaning, reflecting the inner lives of characters who grapple with memory, identity, and moral ambiguity.

From the very beginning of her career, Katherine Anne Porter demonstrated a commitment to artistic precision. Each sentence in her writing is carefully crafted, each word chosen with remarkable intent. Unlike some of her modernist contemporaries who favored radical experimentation, Porter practiced a quieter, more refined form of modernism. Nevertheless, her stories show the hallmarks of the movement — fragmentation, subjective perspectives, symbolic imagery, and a deep sense of disillusionment. Most significantly, her ability to dramatize the psychological and emotional life of her characters set her apart as a writer of rare sensitivity and depth.

Early Influences and Modernist Context

Katherine Anne Porter was born in 1890 in Indian Creek, Texas. Her early life was marked by hardship, including the death of her mother and years of poverty. These experiences influenced her thematic preoccupations with death, suffering, and the fragility of human existence. During the 1920s and 1930s, she spent time in Mexico and Europe, absorbing a range of intellectual and literary influences. Notably, she engaged with modernist peers such as Hart Crane, Ford Madox Ford, and Ernest Hemingway. While she admired the innovation of writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, she carved her own path — blending Southern Gothic elements with modernist techniques.

Moreover, Porter’s Catholic upbringing, though later rejected, left an indelible mark on her worldview. Questions of sin, guilt, redemption, and the search for meaning run throughout her work. In the modernist context, her fiction stands out for its focus on moral and emotional clarity rather than formal radicalism. Still, her stylistic restraint does not mean simplicity. Instead, it reflects a modernist concern with surface control masking inner turmoil. Her fiction is layered, and beneath its calm surfaces lies a profound existential unease.

Flowering Judas and Symbolic Complexity

Porter’s first collection, Flowering Judas (1930), immediately established her as a formidable talent. The stories in this volume are rooted in her experiences in Mexico during the revolutionary period. The title story, Flowering Judas, tells of Laura, a young American woman disillusioned with the ideals of the revolution. Although externally she appears calm and dutiful, internally she experiences deep moral conflict and emotional detachment. This contrast between inner and outer worlds is central to Porter’s modernist vision.

Significantly, Porter employs rich symbolism in this story. The flowering Judas tree, often associated with betrayal and death, becomes a metaphor for Laura’s internal struggle and moral ambiguity. As a modernist writer, Katherine Anne Porter uses these symbols not to deliver clear moral messages but to deepen the emotional and psychological complexity of her characters. The story ends ambiguously, with Laura experiencing a surreal vision of a hanged man offering her communion — a scene heavy with sacrificial and religious imagery, yet unresolved. This resistance to neat conclusions is another trait that places Porter firmly within modernist aesthetics.

Pale Horse, Pale Rider and Psychological Realism

Perhaps Porter’s greatest modernist achievement is her novella collection Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939), which includes three long stories: Old Mortality, Noon Wine, and the titular Pale Horse, Pale Rider. Each of these stories explores the passage of time, the unreliability of memory, and the burden of emotional legacy. However, Pale Horse, Pale Rider remains the most celebrated for its haunting depiction of the 1918 influenza pandemic and World War I.

The novella follows Miranda, a young journalist, as she falls in love with a soldier named Adam. Their brief happiness is soon shattered when both are struck by the flu. Adam dies, and Miranda survives — but barely. The story is not just about physical illness; it is about the psychological trauma of living through a world in collapse. Time becomes disjointed. Dreams, hallucinations, and memories blur together. Porter’s modernist technique is clear: she uses stream-of-consciousness narration and shifting perspectives to mirror the inner disintegration of her protagonist.

Moreover, Miranda’s struggle is not only personal but symbolic. She represents the modern individual — isolated, disoriented, and alienated by forces beyond her control. Her experience with death, war, and sickness aligns with the disillusionment that permeated postwar modernist literature. As a modernist writer, Katherine Anne Porter did not merely depict events; she dramatized their emotional and existential consequences.

The Modernist Use of Time, Memory, and Fragmentation

One of the core features of modernist literature is its rejection of linear time and objective reality. Katherine Anne Porter exemplifies this through her intricate treatment of memory and subjective experience. In stories such as Old Mortality, time shifts frequently, and the narrative unfolds through remembered experiences rather than chronological events. The characters are constantly reinterpreting the past, trying to make sense of family legends, moral values, and emotional wounds. This preoccupation with memory as fluid, unreliable, and emotionally charged is distinctly modernist.

Furthermore, Porter often fragments her narratives. Rather than offering a single, unified perspective, she allows readers to see multiple emotional truths. For instance, in The Jilting of Granny Weatherall, another highly acclaimed story, the narrative centers on an elderly woman reflecting on her life as she lies dying. The reader is taken inside her mind, where past and present coexist. The story shifts between memory and perception, seamlessly blending thoughts, sensations, and regrets. This interiority — a hallmark of stream-of-consciousness modernism — allows Porter to present a deeply human, yet disoriented consciousness.

Porter’s Women: Agency, Constraint, and Modern Identity

Although she never identified as a feminist, Katherine Anne Porter’s fiction offers some of the most nuanced portrayals of women in American modernist literature. Her female characters are complex, introspective, and frequently caught between social expectations and personal desires. They struggle with marriage, autonomy, sexuality, and moral conflict. However, Porter avoids easy classifications. Her women are not merely victims or rebels; they are layered individuals shaped by history, culture, and internal contradiction.

This nuanced approach to female identity aligns with modernist explorations of selfhood and agency. Miranda, a recurring character in several stories, serves as a kind of alter ego for Porter herself. Through Miranda, Porter examines the challenges of being a woman artist, a thinker, and an emotionally vulnerable person in a patriarchal and chaotic world. These portrayals offer a distinctly modernist insight into the fractured, often contradictory nature of human identity.

Stylistic Precision and the Language of Modernism

Katherine Anne Porter’s style is a study in control. Unlike the expansive, chaotic narratives of some modernists, her prose is disciplined and exact. Every word matters. Her language, though elegant and lyrical, never becomes sentimental. This stylistic rigor reflects her belief in form and structure as tools for expressing deep psychological truths. She once remarked, “I shall try to tell the truth, but the result will be fiction.” In this statement lies the essence of her modernist philosophy — truth is elusive, multifaceted, and often only approachable through artifice.

Moreover, her sentences flow with musical cadence, yet they carry emotional weight. Even in moments of apparent stillness, her characters experience inner revolutions. Her language functions like a scalpel — cutting through surfaces to reveal raw emotional truths. Therefore, Katherine Anne Porter as a modernist writer reminds us that restraint can be as radical as experimentation.

Recognition and Legacy in Modernist Literature

Although she did not publish prolifically, Katherine Anne Porter achieved critical acclaim during her lifetime. She won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for her 1962 collection The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter. These honors reflect her standing in the American literary canon, especially as a master of short fiction. Yet her influence extends far beyond awards. She is often cited as an inspiration by later writers for her stylistic clarity and psychological depth.

Importantly, her work continues to be studied for its modernist themes and techniques. Scholars recognize her unique ability to combine regional storytelling with universal concerns. Her legacy within modernism lies not in flashy experimentalism but in emotional authenticity, narrative sophistication, and moral complexity. In this way, Katherine Anne Porter occupies a vital space in the American modernist tradition — distinct, refined, and quietly revolutionary.

Djuna Barnes as a Modernist Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/djuna-barnes-as-a-modernist-writer/

English Literature: https://englishlitnotes.com/category/quiz-history-of-english-literature/

Grammar Puzzle Solved: https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/since-and-for-in-english-grammar/

Notes on English for Class 11: http://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.